The 6 Top Positions in Shooting

Standing position has been the default for the club, the spear, the bow, and the arquebus. It’s the position of mobility, observation, visibility to the commander but how well does it actually work for modern marksmanship?

Firing while standing isn’t the most stable process, though it may be improved with a rifle sling, or with a two-hand hold on a pistol. It affords too much exposure to the return fire, unless tall breastworks, deliberate or improvised, are available.

With these disadvantages, why stay standing?

Mobility, both for going places and turning rapidly. Being able to see over obstacles. Easy reach of various pouches and carriers on the body. Rolling with the recoil of large bore guns instead of absorbing punishing recoil in place. Staying out of mud, puddles, and off rocky ground. The two downsides don’t mean much in non-military close-range shooting typical of competitions and recreational plinking.

Kneeling

Kneeling is also a time-honored position, suitable for bracing a spear or shouldering a musket with some support. Kneeling properly, with the butt of the heel, and the forward elbow ahead of the knee, gives excellent stability for accuracy with long guns and short.

It is fairly decent about allowing the body to sway with recoil. The shooter becomes quite a bit smaller of a target compared to standing. This way, a heavy weapon can be held comfortably for a long time.

Why not kneel all the time?

Grass or other obstacles between you and the target might be too high. Getting into the kneeling position takes time and some people’s knees or ankles don’t bend well. The knee on the ground can find snow, puddles, rocks, or broken glass. Turning to fire left or right becomes a slower process.

Prone

Prone is the newest position, in vogue mainly after the late 19th century. It’s useless with anything but firearms, perhaps a crossbow. Slow for changing directions, slower for changing positions. Recoil transfers to the shooter unmitigated, unless the gun is slowed by a hook or a bipod braced against something, affording limited visibility in the mud, snow, or puddles, perhaps with a helping of broken glass or brick. And yet, this lousy position is the mainstay of military operations and target shooting.

Stability is excellent, and exposure to return fire is minimal. Those two considerations, despite every other disadvantage, have made prone the position of choice for longer range firing. Stability may be enhanced by supports, and by the use of a sling.

Squat, Sit, and Bench

“Rice paddy” flat-footed squat, for those whose knees bend well, is both stable and allows for rapid transitions in and out of the pose. Each elbow rests forward of the respective knee. The stability is almost as good as kneeling, but knees are kept off questionable ground. Recoil absorption is average, and the ability to turn left and right is likewise.

Sitting, with legs open or crossed, has the stability advantage. It’s a slow pose to enter or leave and puts the butt on the ground. It works well for raising the eye level without losing too much accuracy.

Another option requires a sturdy bench, a nice but unlikely thing to have in the field. Supine offers a reasonably stable position at the cost of greater exposure to the ground, along with a very slow adoption process. First used in long-range rifle competitions, with the long barrel rested on one of the feet, supine eventually regained some popularity as an anti-aircraft measure, lately an anti-drone expedient. Neither practice is currently mainstream in the United States.

Project Appleseed and other training organizations provide comprehensive guides and classes focusing on the variety of shooting positions. Knowing them gives marksmen more options for getting accurate hits.

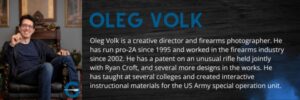

Written by: Oleg Volk, Firearms Photographer