Gunsmithing Experience: 2 Crucial Points to Know

Theoretical knowledge is valuable. Reading the instruction manual, followed by a repair manual, polished off with a tutorial video can go a long way towards competency in all kinds of endeavors, including repair, maintenance, and customization of guns. After all, that’s how it works with electronics, vehicles, and spacecraft, right?

An instruction manual will show what parts make up the item, how to disassemble it, and common pitfalls. Not reading the manual is a sure way to launch springs, damage finish, or just plain fail to complete the process.

A repair manual would tell what tools are needed, how much time may be required, what troubleshooting steps are worth taking. Combined with video tutorials, that goes a long way towards hinting at non-obvious steps, like checking for hairline cracks in metal under the grease layer.

With all those resources, what’s there to argue for instructor-guided experience? The nuances, the intangibles, the details that cannot be quantified.

For example, it is possible to know how much torque is required to remove a screw. If that amount fails, numerous paths are available: more torque, heat, penetrating oil, and more. Some of them would break the screw. Others would damage the finish around it. Oil might work but takes so much time to be suboptimal. Extra leverage might save hands from damage when the screw finally gives but might be difficult to accomplish inside a constricted space.

The Two Keys to Hands-on Experience

The benefit of hands-on experience is two-fold: effective troubleshooting by the instructor witnessing your efforts, and the tactile feedback from tools for diagnosing problems.

If everything is going right, your duty is more akin to being an armorer, not a gunsmith. Gunsmiths, beyond customizing guns, are more often called upon for repairs and even the service manual can’t definitively diagnose a problem without some individual experience added to prior knowledge.

The problem with prior knowledge is its insufficiency, especially when it comes to custom firearms. And the cost of breaking a part may be rendering an entire gun useless if replacements are neither available nor reproducible.

An experienced instructor would know what a change of metal color indicates in terms of heat treating, or what spring progression is reasonable for altering action timing. It’s the massive advantage of experience multiplied by prior learning from mistakes that saves trainees years of trial and error of their own.

Book knowledge is essential—be it on paper, on-screen, or in the form of a video—but not sufficient by itself. It’s possible to dispense with guided instruction, but at the cost of more time, possible injuries, needlessly broken guns, and the reinventing of techniques and methods already discovered.

Unguided hands-on experience remains valuable: only by doing something can a budding gunsmith know what “light sanding with steel wool” feels like, or whether interference works on a part with two surface-hardened objects. And working with reference materials keeps the mind agile by requiring constant critical evaluation of the process and the results, rather than relying on the teacher. Both methods have their place…one is just more expensive in time and parts than the other. The divide isn’t between working with a teacher or with reference materials only, it’s the hands-on vs theory only, without ever putting a file to the metal.

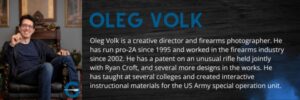

Written by: Oleg Volk, Firearms Photographer